|

|

|

|

Transcendental Interstices: An Ethnographic Exegesis of Shamanic Praxis among the Muramkulukkipattu Malaya Tribe

Dr. Saran S. 1![]()

![]() ,

Dr. Vineetha Krishnan 2

,

Dr. Vineetha Krishnan 2![]()

1 Assistant

Professor and Head, Department of English, University Institute of Technology- Pathiyoor, University of Kerala, Thiruvananthapuram,

Kerala, India

2 Assistant

Professor and Head, Department of English, NSS College Nilamel,

Thiruvananthapuram, Kerala, India

|

|

ABSTRACT |

||

|

All the

characteristics of the ‘Muram Kulukki’ song are

close to the characteristics of shamanism. Connecting with the spiritual

world, reaching a trance state through the repetition of music and dance,

spiritual treatment for healing, unity and togetherness of the community, and

deep respect for the forces of nature are all reflected in this ceremony.

Through this, not only is the spiritual life of a tribal community

strengthened, but also their social ties. ‘Muramkulukkipattu’

is unique in both its social and cultural aspects. Since it is a ceremony

that brings everyone together in the community, it becomes a symbol of unity

and togetherness. Songs have long served as a medium through which tribal

histories and stories are handed down across generations. ‘Muramkulukkipattu’ has given confidence and comfort to

the people in situations where scientific treatment for healing is not

available, and it also has great artistic value. Researchers are studying it

today as part of the folk songs of Kerala. In the research article

“Transcendental Interstices: An Ethnographic Exegesis of Shamanic Praxis

among the Muramkulukkipattu Malaya Tribe,” the

shamanistic performance is explained in the context of treating patients; the

Shaman also offers his audience a performance. What is this performance?

Risking a rash generalisation based on a few

observations, we shall say that it always involves the Shaman’s enactment of

the ‘call’ or the initial crisis which brought him the revelation of his

condition. But we must not be deceived by the word performance. |

|||

|

Received 28 August 2025 Accepted 29 September 2025 Published 01 October 2025 Corresponding Author Dr. Saran

S., srn.s@rediffmail.com DOI 10.29121/Shodhgyan.v3.i2.2025.58 Funding: This research

received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial,

or not-for-profit sectors. Copyright: © 2025 The

Author(s). This work is licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution 4.0 International License. With the

license CC-BY, authors retain the copyright, allowing anyone to download,

reuse, re-print, modify, distribute, and/or copy their contribution. The work

must be properly attributed to its author.

|

|||

|

Keywords: Muramkulukkipattu, Olavanaparam, Shamanic

Praxis, Transcendental Interstices |

|||

1. INTRODUCTION

James George Frazer (1854–1941) was a Scottish social anthropologist. Fraser has considered witchcraft as a primitive science. Ancient tribes performed various types of witchcraft under the leadership of the ‘Gotra’ (lineage), elders, to ward off disease deities and remove different types of plagues. These rituals were mixed with green medicine, and this can also be described as ‘Sahasa Mantravada’ (Black magic for daring acts). In Kerala, the main castes of ‘Adiyar’, ‘Kanthichar’, ‘Malayar’ and ‘Kadar’ have the ancient method of ‘medicine and witchcraft’. The main magical performances are ‘Gaddhika’, ‘Chat’ and ‘Muramkulukki’. This lamp playing song, also known as ‘Peypattu’, is a form of singing performed by the ‘Malayar’ tribal community living in the Peechi-Palappilly and Kodassery hills of Thrissur district. The Malayar people, who live in about ten settlements including Olavanaparambu, Kallichitra, Echippara, Thamaravellachal, Chakkiparambu, Anapadam and Drukkai, are also found in Palakkad and Ernakulam districts.

Since ancient times, humans have been using various methods for healing and spiritual solace. Shamanism is the oldest spiritual practice that existed before scientific medicine and religious systems. A person who connects with the spiritual world and performs rituals for healing is called a shaman. Shamanism, which existed in different forms in various tribal communities around the world, also had a special place in the tribal communities of the hills of Kerala. One of its main incarnations is the ‘Muramkulukkipattu’. The lives of the tribal tribes living in the hills of Kerala are connected to nature. They obtain food and medicine from the forest and see all the elements of nature as divine. The main way they used to deal with problems and illnesses in life was through spiritual rituals. Muramkulukkipattu is a ritual that integrates the social and spiritual elements of their lives.

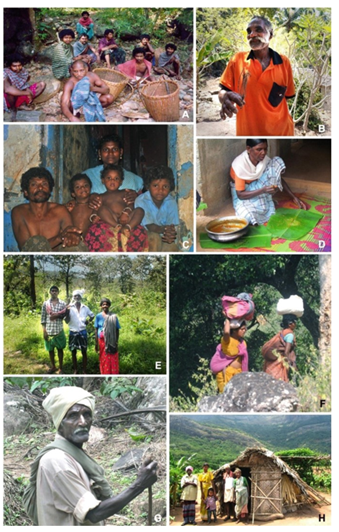

Figure 1

|

Figure 1 Malayarayan Tribes in Kerala |

This art form became known to the outside world during the tribal literacy movement (1994-98). Kunchan Narayanan (60 years old) of ‘Olavanaparam’ (Occult) is the main artist alive today. He was ready to perform this ‘Mantri Kachchand’ (Incantation ritual) in a non-traditional context. The writer has conducted fieldwork in ‘Olavanaparam’ three times, witnessed this performance and gathered knowledge about ‘Chikithsa’ (treatment) with the elders. Today, they do not live in the forests but inside the Harrison Rubber Estate. They live in newly constructed houses provided by the government. The main occupation of the Malays is collecting forest products (MFP). They produce food through hunting, honey collection and harvesting wild tubers.

The person who administers the tribe is called the ‘Elu Moopan’. The priest who practices witchcraft and tribal medicine is the Moopan (Head). The basis of both these positions is tradition, love, and skill in forest knowledge. Every village of the Malays who worship mountain gods and clan deities has a ‘devasthanam’ (Place where God resides). In some places, this is an ‘Alari Thara’ or ‘Pala Thara’ (Alstonia scholaris). ‘Malangkurathi’ is enshrined in a small cot and worshipped. These idols are made of pebbles. The main idols are ‘Malangkurathi’, ‘Bhadrakali’, ‘Kanda Moopan’, ‘Kapiri’, and the spirits of the dead. In addition to witchcraft rituals, the Malays also have dance forms such as Kavarakali, Anakali, Polikali, Kuranakali, Pampukali, and Chodukali.

2. The Soothing Incantation of the Muram Kulukkipattu

At the centre of ‘Muramkulukkipattu’ is the instrument ‘Muram’. The ‘Muram’, a wooden object used for drying and rolling rice, becomes a musical instrument in the hands of the tribes. The sound produced when the Muram is shaken as part of the ceremony becomes music, and songs and chants are added to its rhythm. The ceremony aims to summon spirits, treat the sick, and unite the community. At the beginning of the ceremony, the shaman of the community appeals to the spirits through special songs. When the rhythm of the ‘Muram’ shakes sounds as the background of the ceremony, the participants gain a special mood. The spirits of ancestors, mountains, rivers, and animals are summoned as divine powers, and blessings are sought from them. It is believed that the disease is driven out by placing the sick in the middle of the ceremony and repeating the songs and rhythm.

At the end of the ceremony, everyone sings, dances, and shares food. The disease is caused by various types of ‘pestilences. The Malays believe that it causes many diseases, such as death, panic attacks, and epilepsy. Ghosts and ghosts can be present while walking in the forest, bathing, or travelling alone in the dark. Kunchan Narayanan says that this belief may have arisen from the mystery of the forest, as it was inhabited in the past. The priest is a traditional servant of ‘Malangkurathi’. ‘Muramkilukkipattu’ (Winnowing song) is an attempt to find out the causal information of the disease deities.

The ‘Muram Kilukki’ song is performed in the evening by the light of a lamp. The elder sits in front of the lamp, and the singers sit on the ground in a semicircle on both sides. The afflicted or sick person should sit on the right side in front of the sorcerer. First, water is poured into the Muram, and the Muram begins to be chanted. After a while, traditional songs are sung. First, eighteen zodiac signs are arranged, and the Kollenkode Panikkar, who taught the zodiac signs and the Kuruppan, who taught the magic, are sung. This is done with the Rasi song. The Sun God, who shines like the symbol of the sun, is also praised. This is the song that brings the ‘Karanavas’ and ‘Malangkurathi’ to the ‘Muram’.

The song is called “I will call you when I see you” (58). Secondly, the music is changed, and the guru (Teacher) who comes to the ‘Velaparam’ is sung, ‘Raraaram Guruve’(Hail, O Guru!). This song is where the sorcerer inquiries about which ‘Vata’ (diseases) have caused the harm. At this time, he is meditating, leaning on his pillow, looking at the ‘mura’. When the chain falls from the ‘mura’, he picks it up and puts it back on the ‘mura’. When the chains become entangled, the ‘shaman’ realises that he has a powerful enemy. Awakening the Ganges, removing evil spirits, and prescribing herbal medicines are presented. It gives relief to the patient. After getting the vision of the disease deities in the ‘Murata’, the ‘Malamurti’(Idol adorned with garlands) will clearly tell what kind of magic and medicine this treatment with the patient is, whether it is scientific or not, and what the cause of it. And where and how was it affected? The deity will list the afflictions and ask which of you is affected, and they will be called and questioned.

In modern times, studies on ‘Muramkulukkipattu’ have opened new avenues for ethnology, anthropology, musicology and cultural studies. Studies conducted by researchers on its musical form, lyrics and ritual structure are expanding knowledge of the inner workings of the mental, social and spiritual life of tribal communities. When viewed as a cultural heritage, the importance of Muramkulukkipattu is extremely great. It is essential to try to include it in UNESCO’s list of intangible heritage or in national heritage conservation plans. Because if such traditions are lost, not only that, but the soul of a community will also be lost. To maintain the sanctity and spirituality of ‘Muramkulukkipattu’ in society, efforts should be made to teach and promote it to tribal children and youth. It is essential to include it in educational, cultural activities and research programs.

Figure 2

|

Figure 2 Mannankoothu, Dance-Drama |

The symptoms of this ‘transformation’ begin in the elder when the metallic sound of the chains of the ‘murma’ reaches a tight rhythm from the old one in the same rhythm, and the ‘murma’ is tightened. The ‘kumilzhut’ (Honey drip) is tightened to the stomach. A type of shivering will occur in the body. Along with this, the old songs of the mantra age begin. After singing the part “Che chom kaadare chechem kaadare” (59). quickly, the commandments similar to the totem are recited. This commandment is called ‘vaivattam kadhu’ (Whistling wind). This is a long prose incantation voice that expels the evil. At this time, the body of the ‘shaman’ is a body that has been touched by the goddess / Bhagavati. His body system and breathing change. Kunchan Narayan explains this way:

While singing, there is a movement in the body. Then a fainting spell will come. If the deity is affected, the memory will be lost for a few minutes, and the 'few minutes' is the time when the temple is seen in the murta. The man, terrified by the intensity of this Kali-bada, jumps up and jumps. Then he reaches for the rice. With this rice, he goes to the room where the Karanavans are sitting (in some cases, he goes to the bed where Malangkurathi is installed) and throws the rice. In one corner of the room, two palamutti are placed. (59)

The entire act carries a dramatic essence, resembling a form of Shamanic theatre staged briefly to enthral its devoted spectators. Unlike a simple imitation or reenactment of events, the shaman experiences them anew with full intensity, authenticity, and force. When the performance concludes and he returns to his ordinary state, it can be described, using a concept from psychoanalysis, as a process of abreaction. The home of the soul and the change of the nest (metempsychosis) are part of witchcraft. The tribes know that the shaman with this ability can give mental relief to the patient. The tribal healer who brings freedom and comfort to the mind. The shaman can be called the ‘abreactor’. Shamanism is the manifestation of the essence. The shaman knows the breathing act to do inside the shaman. This means controlling and releasing the magical energy that has been stored in the body. The body’s pulsations and the nerves are all signs of the manifestation of the essence. Throwing the head back, spinning, jumping up suddenly, running and jumping are the shaman's production acts in this manifestation.

An internal meditation process, performed by a Malay shaman, involves yogic shaking of the body with the eyes closed, and the chanting of the mantra to its controlled rhythm, transforming the body into the ‘phenomenon’ of the ‘shaman’. This magical practice involves understanding and unleashing the ‘secrets’ that have been brought to the fore by trapping the invisible forces in rhythm, music, breath control, and body expression. This self-confidence is seen in the shaman. The statements, we can see these forest gods, and we will bring them before our eyes and question them, show this self-confidence. This strength comes from the yogic nature of ethnic music. This music flows from the depths of the forest, knowledge that he has acquired. The epistemology of the shaman is the spiritual knowledge of plants (ethno-botany), animals (ethno-zoology), and ecology.

3. The Musical Instrument-Mantrika Muram

This triangular sari is woven from bamboo or reeds from the forest. After observing a fast for seven days, this ‘murram’ is made traditionally. Although such ‘murrams’ are usually used for agricultural purposes in Kerala, the Malay tribe does not cultivate them. Women do not touch this ‘murram’. After the performance, it is usually hung up in an inner room. It is not taken out on an occasion. Wires are bent and made into links on the ‘murram’, making it look like a chain.

Figure 3

|

Figure 3 Traditional Musical Instruments |

These chains, which are about a meter long, are intertwined to create a metallic sound. There are a few musical instruments made by combining metals in this way in Kerala. In the chat of the tribal audience, the magical sound made by rubbing the instrument called ‘Kokkara’ on the metal is given importance. According to Keith Howard (Ethnomusicologist, musicologist, and anthropologist):

The magical ‘murram’ is touched only after bathing, performing pooja in the ‘kotti’ and purifying the water. The ‘murram kilukippa’ toot is also performed to protect the tribe from evil spells, such as taunts and curses by others. However, this tribal ritual is not used to practice evil magic. The use of magical music with the sound of the gong is a form of good magic and is part of shamanism (Keith Howard 2002, 67).

4. Herbal treatment

After the spirits appear in the courtyard and find the causes of the disease, the sorcerer prescribes remedies. The most important of these is ethnomedicine. The ethno medicine of the Malay community is called ‘Edamunnan’. There is a special song about herbal medicine in the ‘Muram Kulukki’ song. In the song called Pandhu Pachamarunnoru Thariyapole Pachekam:

Let me see if I can find some herbs. I, too, am going to the flower garden. I, too am going to the flower garden. I have gathered a thousand and eighty-one herbs. I am going to the flower garden. Oh, my girl, I am going to the flower garden. One hundred and one herbs, green, let the nerve root rise, green quickly. (63)

‘Pala tree’ (Alstonia scholaris) and other plants used for witchcraft, they refused to tell the names and ingredients of the medicine during the coffee break. However, the ‘panal plant’ (Areca catechu) and the ‘kanjal plant’ (Sapindus trifoliatus) were used. After the ‘Muram Kulukkipattu’, the doctor gives the medicine, and it is to be taken internally, fear is called ‘Pradhasan’. The two small leaves on the stem of this small plant are the ‘Thokhu Kanni’, commonly known as the ‘Ramanama plant’ or ‘Rama thulasi’ (Ocimum tenuiflorum). The leaf in the middle is believed to be female, and the leaf on the right is male. The medicine is taken from the strong leaf in the leaf stalk. The tribal doctors explain that the name of the medicine should not be mentioned and say, “That if you say so, it will not be effective” (69).

Figure 4

|

Figure 4 Herbal Treatment |

The Malays are also known for their rare poisonous medicine. Another remedy used by them is various sacrifices and pujas. Mantramist’s command is an apt example for this. “The enemy was removed by contacting the family god. Mukonu should be performed along with the sacrifice. Mukon Bali and Pancha Bali are important sacrifices. Nail into the bridge or the Kanjir. Sacrifice a chicken and pour its blood at the base of the bridge. All such actions certainly are to psychologically eliminate the fear within the patient. Along with this, the community and the patient get relief.

A shaman, who controls supernatural forces, is also a social psychologist. Shamanism is a vision of the conscious landscape of the world’s primitive cultures. It is not only a form of magic but also has psychological and cultural significance. Shamanism is known for its knowledge of the journeys of human consciousness, spiritual realms, and revelations. It is said that shamanism originated in Siberia. There, egg-shaped percussion instruments representing birth are used for this purpose. The drum, energised, becomes the shaman’s spirit helper, says Keith Howard in his study. “This is therapeutic music that provides relief to the sick and the tribes. Special ways of speaking, commands, (Psycho-acoustic effects) cause changes in the listener” (64).

5. Conclusion

However, over time, due to urbanisation, religious conversion, and the spread of education, the traditional beliefs of the tribes are waning. Today, ‘Muramkulukkipattu’ is often seen only in art programs and on the stages of research organisations. It exists only among some tribes in medical ceremonies and festivals. However, researchers and cultural organisations are trying to preserve it and pass it on from generation to generation.

‘Muramkulukkipattu’ is not an ordinary tribal song. It is the foundation of the spiritual life of the hill tribes. It is a ritual that represents the connection with nature and ancestors. ‘Muramkulukkipattu’, a local incarnation of shamanism, paves the way for healing, social harmony, and spiritual peace. Despite many changes in the current situation, ‘Muramkulukkipattu’ remains a living tradition that represents the life spirit of the tribes. Therefore, it is of great importance to preserve it as a cultural heritage and conduct further studies. The beliefs and customs of tribal people have been passed down from one generation to another. We can say Muramkulukkipattu is an apt example for this. Due to changes in today’s cultural changes and socio-economic conditions, these tribal people lost many inherent things from their generation. We can say that Muramkulukkipattu remains a tribal life tradition. Therefore, its existence can be read as a sign of cultural resistance.

Preservation of tradition is not just nostalgia or sympathy for an outdated custom, but also an obligation to maintain living cultural diversity. In today’s situation, where the world is slowly moving towards uniformity, such special cultural manifestations remind us that human diversity and polymorphism are evident. ‘Muramkulukkipattu’ teaches us as a model that brings together social justice, cultural rights and spiritual heritage. Its deep message is love for nature and coexistence. This tradition reminds us that the spiritual quest of man is fulfilled through the relationships of body-mind-society-nature. “‘Muramkulukkipattu’ is not the property of a single tribe, but part of the entire cultural heritage of humanity. Therefore, researchers, governments, cultural activists, educational institutions, and communities all must work together to study, preserve, and disseminate it” (71). By preserving ‘Muramkulukkipattu’, the spirit of tribal life in the mountains will also survive; when it survives, human cultural diversity and the spiritual wealth of the world will survive

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

None.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

None.

REFERENCES

Glassie, H. (1983). The Moral Lore of Folklore. Folklore Forum, 16(2), 123–151.

Indianetzone. (2025, September 27). Malayarayan Tribe.

Rajagopalan, C. R. (2019). Folklore Arika Sathyangal. Kerala Folklore Academy.

|

|

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

© ShodhGyan 2024. All Rights Reserved.