|

|

|

|

Original Article

SEMANTIC SHIFTS OF INDIAN LOANWORDS IN RUSSIAN: THE CORPUS AND ASSOCIATIVE ANALYSIS

INTRODUCTION

The

intensification of Russian-Indian cultural contacts and the global

dissemination of Indian spiritual practices have prompted the borrowed concepts

of Indian origin to be widely used in everyday life. That entails a

reconfiguration of these concepts through individual and societal usage within

Russian linguistic context, a process involving not only semantic adaptation

but also a transformation of the semantic structure itself. Positioned at the

intersection of linguistics, cultural studies, and Russian language studies,

this research offers a methodological framework for analyzing loanword

assimilation across languages.

The historical

trajectory of Indian loanwords in Russian reflects broader sociocultural

exchanges, from Afanasiy Nikitin’s 15-th century travels to post-Soviet

globalization. Yet, prior studies remain fragmented, focusing narrowly on

derivational or phonetic features Akulenko

and Leontieva (2021) lacking systematic corpus analysis Sharma

(1994) list of 800 words lacks frequency data);

paying insufficient attention to semantic change of borrowed concepts.

Loanwords are a

phenomenon that no language can avoid. The Routledge Dictionary of Language and

Linguistics Bußmann

et al. (2006) defines loanwords as “words borrowed from

one language into another, which have become lexicalized (= assimilated

phonetically, graphemically, and grammatically into the new language)” (2006).

When functioning in a new language, loanwords often undergo conceptual semantic

change – such as widening, narrowing, or shifting Miller

(2015), Julul et

al. (2020) – or associative meaning change, including

metaphor, metonymy, pejoration, etc. Yuniarto

and Marsono (2016).

The study holds

interdisciplinary relevance as it examines a corpus of Indian terms in Russian,

contributing to the understanding of language contact, and provides empirical

data through corpus-based and psycholinguistic methods to track the semantic

change of Indian concepts in Russian.

Thus, this paper

aims to investigate the semantic change of Indian loanwords in Russian by means

of corpus analysis and free association experiment. The study addresses the

following research objectives:

·

To

identify the most frequent words of Indian origin in the National Corpus of

Russian Language (NCRL).

·

To

reveal the most frequent collocations of these loanwords.

·

To

conduct an associative experiment to determine how Russian speakers perceive

Indian loanwords.

·

To

classify the types of semantic changes these loanwords undergo in Russian

cognition.

THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK

Semantic change in

words generally correlates with factors such as age of acquisition,

concreteness /abstractness, emotionality, word length, and arousal Li et al. (2024). According to Li et al., the interplay of

these factors suggests that words engaging broader and more elaborate cognitive

processes are more resistant to change, thus influencing language evolution at

both macro and micro levels (ibid.).

The present study

of Indian loanwords in Russian focuses on several factors of the list above:

word frequency, concreteness, and emotionality. Li et al. (2024) explain that frequently used words with

concrete meanings and strong emotional connotations, being more cognitively

grounded, are prone to retain their original meaning and change less over time.

Conversely, words that are abstract, less emotional, and less frequent tend to

undergo the more significant semantic changes.

Semantic changes

can lead to conceptual shifts, such as re-categorization or change in a

conceptual domain. Such changes are linked to processes of conceptualization

which, according to Moffat

et al. (2015), refer to the acquisition of conceptual

knowledge through “situated conceptualization”. This means that both external

(agents, objects, events) and internal (emotions, introspections) environments

are important in forming concepts Barsalou

(2003). Conceptual knowledge encompasses the

meanings and understandings we have about concepts, grounded in our experience

and contexts in which those concepts appear. Thus, altering any constituent of

the conceptualization process leads to reconceptualization and the emergence of

new semantic meanings.

The study

investigates whether loanwords behave according to the same mechanisms. To

fulfill this aim and outline the current semantic state of Indian loanwords in

Russian, a special methodology was developed.

METHODOLOGY

The data for

analysis were extracted from the most recent edition of the Dictionary of

Foreign Words (2025). The dataset comprises 83 lexemes identified as loanwords

from either Hindi (12 items) or Sanskrit (61 items). Given the historical

relationship between Sanskrit and Hindi – where Sanskrit serves as the

precursor language – both categories were consolidated under the broader

classification of Indian loanwords for this study. It should be mentioned that

the specific pathways borrowings (e.g., via English, as in ‘jungle’, or

Portuguese, as in ‘veranda’) are not accounted for this analysis.

Subsequently, the

lexical units were systematically categorized according to semantic fields

(e.g., religious terminology, everyday vocabulary) and the concreteness /

abstractness criterion. Each term was then subjected to corpus-based frequency

analysis.

To identify

semantic changes and reconceptualization (e.g., the secularization of sacred

terms), an open associative experiment was conducted. The participants were

divided into two age groups: 18-35 years (n 67) and 36+ years (n 68), with a

total sample size of 135 participants. For the experiment, six Indian loanwords

were selected: two abstract words (karma, nirvana), two concrete words

(jungles, avatar), two words with both abstract and concrete meanings (guru,

yoga). Six filler words were also included: three non-borrowed words closely

related to the loanwords (i.e. fate, teacher, fitness) and three general

vocabulary words (i.e. яблоко [yabloko] –

apple, деньги [den’gi] – money, река

[reka] – river). The loanwords were selected based on two criteria: 1) semantic

change probability, i.e. being marked in dictionary as having a transferred

meaning 2) evidence of the transferred meaning’s usage in the corpus compared

to the dictionary definition.

To assess whether

the degree of exposure to Indian culture influences the results, participants

were asked to rate their frequency of encountering Indian culture on a scale

from “never” to “very often”.

The stimuli were

presented in written form and in randomized order to prevent sequence effects.

The resulting list of associations was subjected to quantitative analysis

(frequency of top associations per word) and qualitative analysis

(identification of concreteness / abstractness and positive/negative valence;

comparison of conceptual and associative meaning changes dictionary and corpus

data).

The final stage

involved visualization of semantic clusters and semantic changes for Indian

loanwords.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

INDIAN LOANWORDS: CLASSIFICATION AND FREQUENCY PARAMETERS

The analysis began

with a dataset of 83 Indian loanwords identification in the most relevant

Dictionary of Foreign Words (2025). A lexico-semantic classification yielded

five categories: religious terms (49 items, e.g., Рама

[Rama]– Rama, Вишну [Vishnu] – Vishnu,

карма [karma]– karma,

сансара [sansara]– samsara,

нирвана [nirvana]– nirvana,

йога [ioga]– yoga), health-related terms (2 items,

e.g., асана [asana]– asana,

аюрведа [aiurveda]– ayurveda),

musical terms (3 items, e.g., рага [raga]– raga,

бансури [bansuri]– bansuri,

cитара [sitara]– sitara) and general vocabulary (29items, e.g.,

шаль [shal’]– shawl,

шампунь [shampun’]– shampoo,

джунгли [djungli]– jungles,

веранда [veranda]– veranda). A

subsequent classification based on the of concreteness / abstractness criterion

resulted in 28 abstract words (predominantly from the religious sphere) and 55

concrete words (primarily from everyday vocabulary). In line with Li et al. (2024), we hypothesized that frequent, concrete

words demonstrate greater semantic stability.

The next step

implied the frequency analysis using General Subcorpus of National Corpus of

Russian Language (NCRL) which contains 389 million and provides a

representative sample of language usage. Frequency was measured using the

Instances Per Million (IPM) metric. The analysis confirmed that most Indian

loanwords exhibit low frequency, with IPM scores ranging from 0.01 (e.g.,

нансук – nainsook – [French: nansouk <

Hindi] thin cotton fabric, similar in texture to linen, used for making linen)

to 11,91 (e.g. веранда – veranda –

[English, Portuguese. veranda < Hindi veranda fence, balustrade] a one-story

unheated room with a roof, usually attached to a house along one of its walls).

The corpus usage of the words is illustrated in the examples (1), (2).

(1) At home it had been so clear

that for six dressing jackets there would be needed twenty-four yards of nainsook at sixteen pence the yard, which was a matter of thirty shillings besides the cutting-out and making, and these thirty shillings

had been saved. Tolstoy (1878)

(2) But in the evening - in a carriage, we went into the fields. From

there, we took a public ride, similar to our swing. From there to the Escolta,

there was ice cream. Then, we went to the square, where we listened to

excellent regimental music. After that, we had dinner, drank tea, and sat on

the veranda, admiring the tropical night. The night was moonlit and full

of amazing stars. It was warm, even hot. Goncharov (1859)

From this dataset,

13 of the most frequent loanwords were selected for detailed collocational

analysis. This subset comprised 7 religious terms and 6 general vocabulary

items, reperesenting a mixture of concrete and abstract concepts (e.g.

шампунь [shampun’] – shampoo,

шаль [shal’] – shawl,

веранда [veranda] – veranda,

лак [lak]– laquer, раджа

[radja]– raja, гуру [guru]– guru,

Будда [Budda] – Buddha,

Шива [Shiva]– Shiva, нирвана

[nirvana]– nirvana, карма [karma]– karma,

шаман [shaman]– shaman,

джунгли [djungli] – jungle,

йога [ioga]– yoga). It should be noted that that this

classification is not rigid; a word like ‘guru’ can possess both abstract and

concrete meanings. The word ‘avatar’ was added to the list due to its notably

higher frequency in newspaper (IPM 2,45) and social media (IPM) 7.3 subcorpus,

despite its lower frequency in the General Subcorpus. Furthermore, the corpus

shows the word is used in two grammatical genders: the masculine avatar and the feminine

avatara, reflecting both secular and religious meanings.

COLLOCATION ANALYSIS AND SEMANTIC CHANGES

A collocation

analysis was performed using the NRLC’s Word Portrait Sketch tool, with the

results summarized in Table 1. The data reveal distinct patterns of

assimilation.

Table 1

|

Table 1 Collocations of the Most Frequent

Loanwords of Indian Origin in Russian |

|||||

|

(IPM)

Loanword |

most

frequent* collocations |

|

|

||

|

|

modifier |

Direct

object verb |

Indirect

object verb |

Predicate |

Composed

nouns |

|

(2,4)

шампунь [shampun’]– shampoo |

Cosmetic

(7), therapeutic (6,28), dog’s (3,72) |

Try

IMPERF (5,41), recommend IMPERF (4,34) |

wash

PERF (10,45), IMPERF (8,85), lather PERF (8,41), IMPERF (9,19); wash oneself

up (8,15) |

- |

Balm

(11,22); Conditioner (10,09) |

|

(8,95)

шаль [shal’] – shawl |

down

(9,27); cashmere (9,2) |

throw

over PERF (9,51), IMPERF (8,16) |

wrap

in PERF (10,23); wrap up PERF (9,47); wrap up PERF (9,31); wrap IMPERF (8,3);

wind over PERF (8,36); wind around PERF (8,32) |

Drag

IMPERF (7,45) |

Overcoat

(8,09) |

|

(11,91)

веранда [veranda] – veranda |

Baalbeksky

(8,61); covered (8,26); kitchen (7,51); of a dacha (7,24) |

Build

on PERF (6,33), rebuild PERF (6,18) |

Serve

at PERF (6,99); drink at IMPERF (5,98); |

desert

PERF (5,98); |

Porch

(7,73); annex (7,41) |

|

(8,25)

лак [lak]– laquer |

Alcohol

(8,99), made from shellac (8,9), colorless (8,61) |

Boil

(5,74) |

Cover

IMPERF (9,72), PERF (9,59); paint (8,92) |

Gleam

IMPERF (6,28) |

Polish

(9,47), enamel (9,06), paint (8,56) |

|

(1,09)

раджа [radja]– raja |

Indian

(7,59); hindu (7,56); independent (3,96); local (2,58); young (0,82) |

- |

- |

- |

- |

|

(1,36)

гуру [guru]– guru |

Young

people’s (4,79); Indian (4,22); foreign (3.51), great (0,99) main (0,19) |

- |

- |

Teach

(4,23) |

Teacher

(4,69) |

|

(5,24)

Будда [Budda] – Buddha |

Emerald

(7,03); bronze (5,32); golden (3,47); alive (2,53) |

Meet

(0,79) |

|

Stand

(0.67), sit (0,23) |

Bodhisattva

(9,49); buddha (9,36); God (4,25) |

|

(1,03)

Шива** [Shiva]– Shiva |

- |

- |

- |

- |

God

(0,04 IPM) |

|

(1,58)

нирвана [nirvana]– nirvana |

Buddhist

(7,81); full (0,85), real (0,06) |

Obtain

PERF (4,46), achieve PERF (4,46) |

sink

into PERF (6,58); plunge IMPF (6,51); be plunged IMPF (6,27); fall into IMPF

(3,99). PERF (3,85) |

- |

Samsara

(10,38); non-existence (8,940; |

|

(1,92)

карма [karma]– karma |

Group

(5,3); negative (5,22); bad (3,15); ill (2,61); personal (2,4); public

(2,34); good (1,05); human’s (0,95) |

Work

off IMPERF (6,38); correct IMPERF (4,73); spoil PERF (3,87); change PERF

(3,21) |

- |

- |

Reincarnation

(10,89); karma (10,77) |

|

(6)

шаман [shaman]– shaman |

Tuvinian

(9,57); buryat (8,2), altaic (7,43); tungus (7,22); Indian (6,29) |

Call

PERF (3,56); invite (3,04) |

Dance

IMPERF (4,63); hand in PERF (2,46); give PERF (1,49); |

Perform

the kamlanye ritual IMPERF (7,03); travel IMPERF (5,52) |

Wizard

(9,25); lady-shaman (9,09) |

|

(4,49)

джунгли [djungli] – jungle |

Impassable

(8,72); Peruvian (8,52), Amazonian (8,49); impenetrable (7,94); tropical

(7,94); African (7,35); Australian (7,28); grassy (7,15); neon (7,05) |

Clear

away IMPERF (6,93); inhabit IMPERF (5,74) |

Get

lost PERF (7,38); force one’s way IMPERF (7,35) |

Surround

IMPERF (5,06) |

Savanna

(9,12); desert (6,67) |

|

(2,61)

йога [ioga] – yoga |

Indian

(7,08); Tibetan (6,39) |

Practice

IMPERF (7,47) |

Go

in for IMPERF (4,13); be keen on IMPERF (3,98) |

Help

IMPERF (2,94) |

Meditation

(8,88); starvation (8,84); Buddhism (7,89); physical training (7,33) |

|

(2,45**,

7,3***) Аватар [avatar] – avatar |

Cameron’s

(9,2); three-dimensional (6,48) |

acquire

PERF (7,05) |

Stay

PERF (3,69) |

Force

out PERF (6.07); retain IMPERF (4,55); |

Titanic

(11,2); overlord (10,52); avatar (9,42); mongrel (9,03) |

|

Legend: * LogDice metric is used; PERF – perfective form of the

verb; IMPERF – imperfective form of the verb; Shiva in not represented in

Word Portrait Sketch of National Corpus of Russian language; ** IPM and

collocations in Table are presented according to Word Portrait Sketch in

newspaper corpus; *** data presented according to Word Portrait Sketch in

social networks corpus |

|||||

The collocation

analysis shows that some loanwords, particularly anthroponyms like ‘Shiva’ and

‘Buddha’ preserve their original meaning and do not undergo any changes.

Similarly, as predicted in Li et al. (2024), high-frequency concrete nouns like ‘shawl’,

‘laquer’, ‘veranda’, ‘shampoo’, exhibit no semantic changes, collocating

primarily with wirds related to their core functions and properties.

However, the

concrete noun ‘jungles’ demonstrate a significant semantic extension. While the

dictionary defines its transferred meaning as referring to dangerous urban

neighborhoods or environments of moral degradation, the corpus data reveal a

more nuanced picture. The metaphor is frequently neutralized, used to describe

dense or illuminated cityscapes without inherent negative connotations, as seen

in Examples (3) and (4).

(3) We wandered with Panyushkin through the stone

jungle of the multilevel Monte Carlo, watched the changing of the guard at the

Grimaldi Palace, and saw the antique cars of Prince Rainier. Karabash

(2002)

(4) Herman drove through Moscow at night and

admired its lights and neon jungle, brightly glowing-colored signs and

advertisements. Rostovsky

(2000)

Furthermore, the

term underwent abstraction, metaphorically describing complex and impenetrable

systems, such as “the mathematical jungles of quantum string theories” (Example

5):

(5) Explaining how three-dimensional membrane

worlds "crystallize" in a multidimensional space with six or seven

extra dimensions would lead us into the mathematical jungle of quantum string

theory, various ways of compactifying (convolving) extra dimensions,

topological features of extra dimensions, and other very difficult and abstract

problems. Barashenkov

(2003)

The abstract

loanwords, such as ‘nirvana’ and ‘karma’, which have low frequency ranks, show

clear signs of semantic shift, consistent with the hypothesis. The collocation

profile of ‘nirvana’ centers on the conceptual frame of a “state” that one can

“sink into”, “plunge into” or “fall into” . This has facilitated a shift from

religious term to a general one for a state of bliss or relaxation, as in the

Example (6).

(6) At this time, their precious little feet are

washed, massaged, cajoled and in every possible way appeased to the full state

of foot nirvana. Shigapov

(2013)

Similarly, ‘karma’

was assimilated into common lexis, developing a pronounced negative connotation

(e.g., collocations bad, wrong). It frequently collocates with adjectives like

group, folk, human, personal. This reflects a reinterpretation where ‘karma’

signifies not just personal consequence, but also collective responsibility

(Example 7). In many contexts, it overlaps with the Russian key cultural

concepts of fate Stepanov (2004), which

implies predestination rather than self-determined consequence (Example

8). In other instances, it is used

synonymously with удача [udacha] – luck, as seen

in the phrase карма

подмигнёт [karma

podmignyot] – karma will wink (Example 9), a calque of the Russian idiom

удача

улыбнется [udacha

ulibnyotsya] – fortune smiles upon someone, that means «to be on roll».

(7) The real spirit that gave rise to the idea of

group karma is the spirit of nationalism. Pomerants

(1980)

(8) Mousie Rex: Oh, I guess that's my karma — I've

been on the editorial board all my life.…; -) Nashi

Deti: Podrostki [Our Children: Teenagers] (2004)

(9) Damn it. Okay, karma will wink at her again. I

bargain and discount an art album to a regular customer. Permyakov

(2016)

The loanwords,

‘guru’ and ‘yoga’, which straddle abstract and concrete meanings, exhibit

complex changes. The collocation analysis for ‘guru’ indicates a semantic

widening from a strictly religious “spiritual teacher” to a secular “mentor” is

in “gurus of the information world” (Example 10).

(10) Also, one of

the undisputed gurus of the information world, one of the creators of the Apple

computer, Steve Wozniak, did not disdain to take part in the show. Latkin

(2003)

Concurrently the

corpus provides evidence of pejoration, where the term is used ironically or

critically within quotation marks to denote a charlatan or leader of dubious

sect (Example 11). In spoken language that is marked by the context and the

prosody.

(11) Hence the

prosperity of all kinds of "gurus", psychoanalysts, sects and other

saviors of people from themselves, without whom, it seems, a good third of the

American population cannot do. Vzglyad

Vladimira Bukovskogo (1997).

The loanword

‘yoga’ retains conceptual link to Indian culture in its collocations (e.g.,

индийская [indiyskaya] –

Indian) Table 1. However, its primary meaning in the corpus

has shifted decidively toward the second dictionary definition: a system of

physical exercises. It is now firmly fixed in the semantic field of fitness and

wellness, often mentioned alongside athletics and other fitness programs

(Example 12), while its meaning as a spiritual practice appears less frequently

(Example 13).

(12) It's almost

impossible to isolate something. Some people like yoga, others like athletics.

I can list only a few successful programs that are currently in demand by the

fitness audience. Gurova

and Lukashov (2014)

(13) Yoga in this

case is considered as a spiritual practice in general. Rogov

(2012)

In summary, corpus

data reveal a spectrum of semantic changes, ranging from stability in

high-frequency concrete terms to significant reconceptualization in abstract

and less frequent words. The following section investigates whether these

documented semantic changes are reflected in the language consciousness of

native speakers.

OPEN ASSOCIATIVE EXPERIMENT: RESULTS AND ANALYSIS

The open

associative experiment yielded a total of 2,810 reactions, of which 1,746 were

reactions to the six target Indian loanwords’ stimuli (an average of

approximately 300 responses per stimulus). While most reactions were single

words, some participants provided phrases. All responses were included in the

analysis, even if participants provided fewer than the requested three

associations. Some of them (in personal

feedback) attributed this to inattention when reading the task instructions, as

the experiment was conducted online via link without direct researcher

supervision.

An initial

analysis of participants’ self-reported exposure to Indian culture revealed

minor differences between age groups, with a general trend of younger

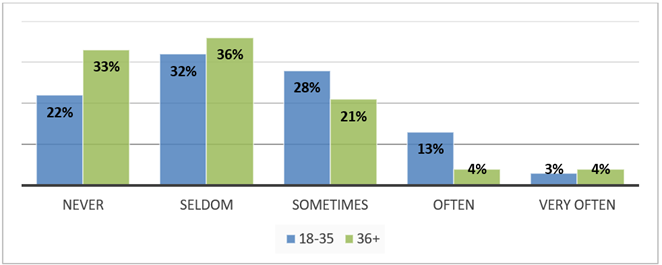

participants reporting slightly higher exposure Chart 1. However, as the majority of participants

(about 60 %) across all groups reported rare exposure, age and cultural

familiarity were not treated as primary variables for the subsequent

association analysis.

|

Chart 1

|

|

Chart 1 Exposure to Indian Culture Among Age

Groups |

For each loanword,

the ten most frequent associations were analyzed quantitively, whole the full

set of responses, including single-occurrence associations, was subjected to

qualitative thematic analysis. The results are summarized below and visualized

(Mauri et al. 2017) in a network diagram Figure 1.

|

Figure 1

|

|

Figure 1 Network of Associations to Indian

Loanwords in Russian Language |

JUNGLE

(CONCRETE)

The associative

field for ‘jungles’ is dominated by its primary meaning. It is perceived as a

hyponym of лес, (forest’ – 10%), with associations clustering

around its physical constituents: geography and terrain type (e.g. tropics,

amazon, Amazonia, Africa, Vietnam); flora (e.g. palm trees, fruits, orchids,

bushes), fauna (snakes, tigers, crocodile, parrots, elephant, panther), and

atmosphere (e.g. dampness, rain, darkness, humidity, heat, warmth). A

significant cluster of associations (Mowgli (6%); Balu, Bagheera, Kipling –

single-occurrence associations) stems from Redyard Kipling’s The jungle book,

indicating the profound grounding of the concept as this literary work is

taught in primary schools of Russia. Popular culture (media), especially the

images of Mowgli and Tarzan, had a huge impact on perception and reflected in

the corresponding associations (e.g. Mowgli, Tarzan, Jumanji). The negative

transferred meaning (“a dangerous environment”) is represented in the

reactions: danger (4%), fear, impassability, unknown, death. Notably a positive, romanticized cluster

emerged (e.g. nature, adventure, mystery, vacation, hunting, hiking), which is

not yet evident in the corpus data, suggesting an emerging connotative shift.

AVATAR

(CONCRETE)

The associative

field of ‘avatar’ is divided between two modern, secular meanings, with its

original religious sense nearly eclipsed. The dominant cluster is media

related, driven by James Cameron’s film Avatar (e.g., film – 16%, blue – 7%)

and the animated series Avatar: The Legend of Aang (e.g., Aang, Cartoon,

Element, Water, Magic, Legend, Anime). The second major cluster is digital,

relating to online identity (e.g., photo – 8%, picture – 6%, account – 3%,

social network – 2%, character – 3%). The original religious meaning

(incarnation of a deity) was found only in single-occurrence responses (e.g.,

deity, incarnation, Buddhism, Hinduism, God, spirit, body), confirming a

near-complete semantic shift in popular consciousness from sacred to digital

and cultural spheres.

GURU

(CONCRETE/ABSTRACT)

The associations

for ‘guru’, confirm its metaphorical widening to secular contexts. The most

frequent responses, teacher (21%) and mentor (14%), align with its dictionary

definition as a transferred meaning (2. Transfer. About the teacher, mentor

[Dictionary of Foreign Words 2025]). A strong cluster signifies someone of high

expertise (master – 10%, professional – 7%, expert, credibility – 2%,

proficient – 6%, trainer <1%, etc.), who leads, teaches and transmits

knowledge (wisdom (3%), wise (3%),

knowledge (<1%), experience (<1%), intelligence (<1%), smart (<1%),

cognition (<1%), philosopher (<1%), visionary (<1%), prophet (<1%)

etc.). However, a distinct pejorative cluster also emerged (e.g. charlatan,

conman, sect, jerk, scam, submission), indicating a critical or skeptical view

of self-proclaimed experts. Associations related to the original Indian context

(e.g. India, yoga, meditation, philosophy, East, religion, monk, Tibet, Zen,

lotus, enlightenment, spirituality) were minor and of single-occurrence, highlighting

the concept’s detachment from its cultural origins.

YOGA

(CONCRETE/ABSTRACT)

The associative

field for ‘yoga’ demonstrates a clear dominance of its concrete, secular

meaning. The largest cluster frames it as a fitness activity (e.g., sport – 7%,

stretching – 7%, exercise – 3%, body flexibility <1%, body, pilates,

gymnastics, physical education, endurance, strength, exercise, aerobics) with

associations related to practice (e.g., breathing – 3%, mat – 2%, practice –

4%, pose – 1%, asanas, group, hobby – 1%, coach) and physical / mental benefits

(e.g., health – 8%, tranquility – 5%, relaxation – 5%, Meditation – 3%, harmony

– 2%, balance, confidence, beauty, benefit, stability, resilience, peace of

mind, rest, pacification, peace, enjoyment, happiness, freedom). However, there is a number of negative

responses (e.g. heresy, hard, sectarians, difficulties, a type of body abuse),

that reveal skepticism towards the practice and the philosophy. The abstract,

philosophical meaning associated with Indian spirituality was a minor cluster,

represented by single-occurrence words (e.g., Zen, nirvana, India,

spirituality, hatha, wisdom, Hinduism, Buddhism, mindfulness, asceticism,

purification, philosophy of being, self-discipline, east, lotus (symbol)). This

confirms a major conceptual shift where ‘yoga’ is primarily understood as a

wellness practice rather than a spiritual discipline.

NIRVANA

(ABSTRACT)

The associations

for ‘nirvana’ are split between two unrelated semantic poles. The first, and

dominant refers to the American rock band Nirvana and its leader Kurt Cobain

(e.g., band – 6%, music – 3%, Cobain, Kurt Cobain <1%, rock, song, Pank,

scene, t-shirt), sometimes with negative reactions (e.g., bullshit, cheating,

dope, drugs, addict, get drunk, forget). The second pole represents a

simplified, psychological understanding of the term as a state of extreme calm,

bliss and relaxation (e.g., state –3%, calmness – 6%, tranquility – 6% (shared

with stimuli ‘yoga’), peace – 2%, rest – 4%, blissout / pleasure – 6%). The

nirvana state is understood by means of related concepts like meditation (2%),

astral, trance, purification, self-discovery. This pole is represented by a

group of reactions that reveal the metaphoric comprehension of the notion (e.g.

harmony, freedom, goal, achievement, paradise, emptiness, nothingness,

everything, being, utopia, non-existent, detachment, indifference – like a lack

of passion) that range from neutral to meliorative. The original Buddhist meaning of cessation of

sufferings was found only in the periphery of associative field (e.g.,

Buddhism, enlightenment, Zen, buddha, extinction – the key aspect of nirvana is

the extinction of suffering, samsara, emptiness – sunyata is an important

concept, liberation, rebirth, atman, Tibet, India, Hinduism, philosophy,

spirituality). This reveals a profound transformation: a sacred, complex

concept was largely replaced by a band name and a vague synonym for relaxation

KARMA

(ABSTRACT)

The associative

field for ‘karma’, that “In Buddhism, Hinduism and other religions of the East,

is a set of actions committed by a person and their consequences that determine

his fate and the specificity of his rebirth and reincarnation” [Dictionary of Foreign

Words 2025], shows a near-total loss of its philosophical meaning. The

associations referring to the Indian origin are minor and primary

single-occurred (e.g., India – 2%, Buddhism, Esotericism, Energy, Aura, Soul,

Samsara, Rebirth, cyclicity, Moksha, Maya, Nirvana, Spirituality – 1%,

Philosophy – 1%). It is overwhelmingly assimilated into the Russian conceptual

domain of судьба [sud’ba] – fate (15%), a

concept characterized by fatalism (e.g., inevitability, predestination, the

cross, the burden, hopelessness, hopelessness) and external forces (e.g., doom

– 2%). Fate in Russian is defined as 1. «A course of events, a combination of

circumstances, that develops independently of a person's will; 2. Destiny,

doom, life path» [Kuznetsov, 2000]. A second major cluster frames it as

mechanism of retribution (e.g., punishment – 4%) respond – 4%, justice – 3%,

boomerang – 3%, revenge – 2%, responsibility – 2%), for person’s actions (e.g.,

act – 2%, action – 1%, sin – 1%, choice, mistakes, merit, be honest, right

etc.), almost exclusively with negative connotations (e.g., bad – 1%, negative

<1%, evil <1%, black, except for justice that is neutral in Russian

language). The associations highlight a fundamental cognitive reinterpretation:

the original Indian concept of ethical causality and personal responsibility

has been reshaped into a fatalistic notion of inescapable punishment for

misdeeds.

SYNTHESIS: CORPUS AND ASSOCIATIVE EXPERIMENT DATA ON SEMANTIC CHANGES

The open

associative experiment revealed some semantic changes in meaning structures of

Indian loanwords. The Table 2. synthesizes the semantic changes identified

through both corpus and associative analysis.

Table 2

|

Table 2 Semantic Changes of Indian Loanwords in

Russian |

|||||||||||||

|

|

concrete |

concrete/abstract |

abstract |

||||||||||

|

jungles |

avatar |

guru |

yoga |

nirvana |

karma |

||||||||

|

c |

a |

c |

a |

c |

a |

c |

a |

c |

a |

c |

a |

||

|

Conceptual semantic change |

Widening |

|

|

|

|

+ |

+ |

+ |

|

|

|

+ |

|

|

Narrowing |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Shifting |

|

|

+ |

+ |

|

|

|

+ |

+ |

+ |

|

+ |

|

|

Association change |

Metaphor |

+ |

+ |

|

|

|

+ |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Metonymy |

|

|

+ |

+ |

|

|

|

|

|

+ |

|

+ |

|

|

Pejoration |

|

|

|

|

+ |

+ |

|

+ |

|

+ |

+ |

+ |

|

|

Melioration |

|

+ |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Neutralization |

+ |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Legend: c – Based on

Corpus Analysis, a – Based on Open Associative Experiment Analysis |

|||||||||||||

The results

indicate that semantic narrowing was not observed for any of the target words.

Pejoration was the most frequent associative change, affecting ‘guru’

(perceived as charlatan), ‘yoga’ (as a hard workout exercise), ‘nirvana’ (as a

state if drug intoxication,) and ‘karma’ (as a hand of justice for bad

deals). Widening (e.g., ‘guru’ as a

professional in general, ‘yoga’ as a type of fitness and ‘karma’ as a synonym

of luck), and conceptual shifts, particularly secularization (e.g., ‘avatar’ –

a film character and image for social media, ‘yoga’ – secular practice

nowadays, nirvana’ – instant pleasure, and ‘karma’ as boomerang) were also

prevalent among abstract and dual-meaning words. Metaphor was a key mechanism

for concrete words like ‘jungles’ and ‘guru’, while metonymy was observed for

‘avatar’, ‘nirvana’, and ‘karma’. Melioration and neutralization are minor and

observed only in concrete ‘jungles’ (neighborhoods of big cities that are not

always dangerous but dense or illuminated, and place for adventures (that is

positive in Russian culture).

The data strongly

support the hypothesis that low-frequency, abstract loanwords are most

susceptible to semantic change. Abstract loanwords underwent more than three

types of changes on average, whereas concrete words underwent fewer than three.

As the target words were emotionally neutral, the results highlight word

frequency and concreteness as the primary factors driving semantic changes in

loanwords, confirming they behave similarly to native vocabulary in this regard

Li et al. (2024). The associative experiment also proved

valuable in capturing emerging changes (e.g., positive framing for ‘jungles’)

not yet fully conventionalized in written corpus.

CONCLUSION

The study provided

a comprehensive analysis of the integration and transformation of Indian

loanwords in the Russian language by combining corpus-based and

psycholinguistic experimental methods. The findings reveal a complex landscape

of semantic assimilation, characterized by significant semantic changes that

reflect the interplay between global cultural trends and local linguistic

tradition.

The research

confirms the hypothesis, aligned with Li et al. (2024), that less frequent and more abstract

loanwords are particularly prone to semantic change. The data demonstrates that

relevantly frequent concrete loanwords like ‘shampoo’ and ‘veranda’ are

resilient to semantic change. In contrast, abstract and less frequent terms of

religious or philosophical origine, such as ‘karma’, ‘nirvana’, ‘yoga’

underwent profound reconceptualization.

The key semantic

changes identified include:

Semantic shift

that could be called secularization. Sacred concepts largely lose their

original religious and philosophical meaning. ‘Karma’ is predominantly

understood in modern Russian as a mechanistic “boomerang” of punishment for

misdeeds or as inescapable fate, overlapping with the Russian concept of

судьба [sud’ba]. Similarly, ‘nirvana’ is

perceived either through lens of Western pop culture (the rock band) or as a

simplified state of blissful relaxation, a far cry from the Buddhist ideal of

suffering cessation.

Widening and

metaphorization that enabled several loanwords develop new meanings. The term

‘guru’ metaphorically extended to denote an expert in any field, but this

extension is accompanied by a potential pejorative sense, implying a

“charlatan” or “sect leader”. The semantic field of ‘yoga’ also widened to

emphasize, apart from spiritual, physical exercise and fitness, sometimes

viewed skeptically as difficult.

The unification of

corpus data with associative experiment results proved methodologically

fruitful. While the corpus provides evidence of established usage trends, the

associative experiment captures the living, often pre-lexicalized, perceptions

of speakers, revealing shifts – such as the romanticized view of ‘jungles’ as a

place of adventure – that is not yet fully reflected in written texts.

In summary, the

borrowing of Indian loanwords by Russian is an example of a profound cognitive

and cultural adaptation. These language units were not passively absorbed but

actively reconfigured, their meanings reshaped by frequency of their use, their

abstract nature, and their encounter with the dominant concepts of Russian and

globalized contemporary culture. This study underscores that lexical borrowing

is not merely a linguistic process but a core mechanism of cultural

translation.

While this study

achieved its goals, is not free from limitations, including its reliance on a

single dictionary and the use of only the basic subcorpus of the NCRL for

quantitative parameters. The associative experiment, while informative,

involved a limited number of participants (n=135). Future research could expand

the participant pool, incorporate data from other subcorpora (e.g., spoken or

regional), and undertake a comparative analysis with the assimilation of Indian

loanwords in other languages.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

None.

REFERENCES

Akulenko,

E. A., and Leontieva, V. N. (2021). Lexemes of Indian-American Origin in the Word-Base System of the

Modern Russian Language. In The Life of Language in Culture and Society:

Collection of Scientific Articles (105–111). Minsk State Linguistic University.

Barashenkov, V. (2003). Veren Li Zakon Nyurona? [Is Newton’s Law Correct?]. Znanie—Sila (Knowledge Is Power), (1), 85–91.

Barsalou, L. W. (2003). Situated Simulation in the Human Conceptual System. Language and Cognitive Processes, 18(5–6), 513–562. https://doi.org/10.1080/01690960344000026

Bußmann,

H., Kazzazi, K., and Trauth, G. (2006). Routledge Dictionary of Language and

Linguistics (Taylor and Francis e-Library ed.). Routledge.

Goncharov, I. A. (1859). Letters.

Gurova, T., and Lukashov, I. (2014). Regulyarnyy Fitnes [Regular Fitness]. Ekspert.

Institute of Linguistic Research, Russian Academy of Sciences. (2025). Dictionary of Foreign Words.

Julul, A. A., Rahmawati, N. M., Kwary, D. A., and Sartini, N. W. (2020). Semantic Adaptations of the Arabic Loanwords in the Indonesian Language. Mozaik Humaniora, 19(2), 135–147. https://doi.org/10.20473/mozaik.v19i2.14584

Karabash, A. (2002, February 4). Three Days in Monaco. Domovoy.

Kuznetsov, S. A. (2000). Bolshoy Tolkovyy Slovar Russkogo Yazyka [Large Explanatory Dictionary of the Russian Language]. Gramota.ru.

Latkin, A. (2003, January 22). Demonstrator Sovesti. Znamenitomu Khakeru Razreshili Vykhodit’ V Internet [A Demonstrator of Conscience. The Famous Hacker Was Allowed to Access the Internet]. Izvestia.

Li, Y., Breithaupt, F., Hills, T., Lin, Z., Chen, Y., Siew, C. S. Q., and Hertwig, R. (2024). How Cognitive Selection Affects Language Change. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 121(1), Article e2220898120. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2220898120

Mauri, M., Elli, T., Caviglia, G., Uboldi, G., and Azzi, M. (2017). RAWGraphs: A Visualisation Platform to Create Open Outputs. In Proceedings of the 12th Biannual Conference on the Italian SIGCHI Chapter (Article 28). ACM. https://doi.org/10.1145/3125571.3125585

Miller, R. (2015). Trask’s Historical Linguistics (3rd ed.). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315728056

Moffat, M., Siakaluk, P. D., Sidhu, D. M., and Pexman, P. M. (2015). Situated Conceptualization and Semantic Processing: Effects of Emotional Experience and Context Availability in Semantic Categorization and Naming Tasks. Psychonomic Bulletin and Review, 22(2), 408–419. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13423-014-0696-0

Nashi Deti: Podrostki [Our Children: Teenagers]. (2004).

National Corpus of Russian Language. (n.d.). National Corpus of the Russian Language.

Oreshnikov, A. V. (1925). Dnevnik [The Diary].

Permyakov, A. (2016). Petushki—Moskva. Poyekhal [Petushki—Moscow. Gone]. Volga.

Pomerants, G. (1980). Son O Spravedlivom Vozmezdie (Moy Zatyanuvshiysya Spor) [A Dream of

Fair Retribution (My Protracted Dispute)]. Sintaksis, 8, 122–147.

Rogov,

O. G. (2012).

Kino, Kotoroye Mozhet Izmenit’ Zhizn’. Vashu? [A Movie That Can Change Your

Life. Yours?]. Volga.

Rostovsky, A. (2000). According to the Laws of the Wolf Pack. Vagrius.

Sharma,

R. (1994). Indian

Exotic Vocabulary in Russian [Abstract of the Dissertation of the Candidate of

Philological Sciences, Minsk State University].

Shchapova, G. (2020). Mir, Ne Trognutyy Tsivilizatsiey [A World Untouched by Civilization].

Znanie—Sila, 6, 45–51.

Shigapov,

A. S. (2013).

Bangkok I Pattaya. Putevoditel [Bangkok and Pattaya: Travel Guide]. AST.

Tolstoy,

L. N. (1878).

Anna Karenina.

Vzglyad Vladimira Bukovskogo [Vladimir Bukovsky’s View]. (1997). Znanie—Sila.

Yuniarto, H., and Marsono, S. U. (2016). Semantic Change Type in Old Javanese Word and Sanskrit Loan Word to Modern Javanese. LLT Journal: A Journal on Language and Language Teaching, 19(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.24071/llt.v16i1.262

|

|

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

© ShodhGyan 2026. All Rights Reserved.